Robin Hood and me in the 1990's outside the Castle Wall.

Showing posts with label Nottingham. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nottingham. Show all posts

Nottingham's Robin Hood Statue

|

| The duplicate statue of Robin Hood |

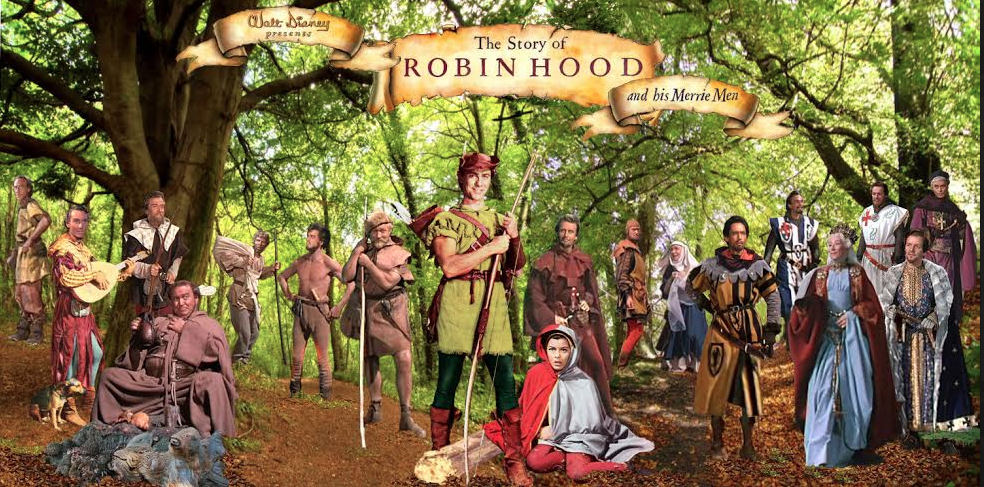

Four months after the premier of Walt Disney's film The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, the city of Nottingham, unveiled a statue to their world famous outlaw, by the castle walls, in the presence of the Duchess of Portland.

|

| James Woodford working on his statue of Robin Hood |

The ceremony took place on July 24th 1952 on Castle Green, in a specially landscaped area at the foot of Castle Rock, in the remains of the old moat, by local architect Cecil Howitt. The seven foot statue, including four bas-relief plaques were a gift to the city, by local businessman Philip E. Clay and was designed and cast out of half a ton of bronze, one inch thick, by Royal Acadamician, James Woodford (1893-1976) in his studio at Hampstead.

|

| The Robin Hood statue today at Nottingham Castle |

Woodford was the son of a lace designer and was born in Nottingham. He attended the Nottingham School of Art and after military service during the First World War he trained at the Royal College of Art in London.

A year after his statue of Robin Hood was unveiled at Nottingham Castle, James Woodford RA was commissioned to carve a set of ten heraldic figures out of Portland Stone, to be placed at the entrance of Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. These heraldic beasts were selected from the armorial bearings of her royal ancestors and can be seen today along the walkway between Palm House and the pond at Kew Gardens.

The bronze statue of Robin has now been copied by experts of Nottingham University and the replica has recently been flown to China as a gift to Nottingham's twinned city - Ningbo.

Sir Richard Foliot and Jordan Castle

Albie’s input on this site regarding the history of

Nottinghamshire and in particular Sherwood Forest has been invaluable. One of the many interesting topics he has raised

is the ancient history of the Nottinghamshire village of Wellow. A while ago

Albie sent in some great pictures of the May Day celebrations around its unique,

permanent maypole by the village children. The tradition still remains to this

day that whenever a new pole is needed, it is cut from nearby Sherwood Forest.

And it is the links with Sherwood and the legend of Robin

Hood that make the ancient village of Wellow fascinating. In particular is the

knight who owned the castle near the village. Today it is known as Jordan

Castle, but Wellow Castle, as it was once known, was owned by a local

Nottinghamshire knight called Sir Richard Foliot whose conduct had remarkable

similarities with Sir Richard at the Lee in one of the oldest ballads of Robin

Hood.

In the Geste of Robyn Hode (1495), the knight protects the outlaws in his:

‘....fayre castell

A little within the wood,

Double ditched it was about,

And walled by the road.’

Jordan Castle, as it is known locally, was the inheritance of a Yorkshire knight known as Jordan Foliot who had served in the armies of King John. It came to him in 1225 and later was often visited by Henry III and his retinue when travelling north. Because of his hospitality to the monarch, Jordan was rewarded with deer to stock his park at his nearby lands at Grimstone. After Jordan’s death in 1236 his young son Richard Foliot (d.1299) was allowed to immediately inherit his father’s lands in Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, followed in 1252 with a charter of free warren. This gave him the right to control the hunting of the beasts on his estates. In 1268 King Henry III granted Foliot permission to hold a market and fair near his castle at Wellow.

Foliot’s castle did match the description in the Geste of

Robyn Hode very closely. It was a ringwork castle of the late 11th

and 12th century and included a ditch, a wall of stone and lime, and a moat. It

stood on high ground just outside the boundary of Sherwood and was probably the

manorial centre of the nearby village of Grimstone. In March 1264 Foliot was

given licence by the king to fortify and crenellate it.

In the Geste Robin is betrayed by the Sheriff of

Nottingham after an archery contest. A hue and cry is raised and eventually

Little John is wounded in the knee. They

take refuge in the castle of Sir Richard at the Lee, who welcomes them - the

castle gates are shut and they feast in safety. But eventually the castle is

put under siege by the sheriff.

It appears that Richard Foliot also had connections with

outlaws, in particular the notorious Roger Godberd and his partner in crime

Walter Devyas. Godberd, a former member of the garrison at Nottingham Castle led

a large outlaw band that had poached in Sherwood, murdered and robbed throughout

Nottinghamshire between 1266 and 1272. He

is often put forward by scholars as a possible prototype of Robin Hood.

The Sheriff of Nottingham, Reginald de Grey was given

£100 by the Royal Council to capture Godberd, which he did ‘manfully’. In

October 1271 Foliot was given power of safe conduct and ordered to ‘conduct

Walter Deyvas charged with divers trespasses to the king.’

But Richard Foliot refused to do so and was shortly

afterwards accused of harbouring both Godberd and Devyas and other wrongdoers. The

Sheriff of Yorkshire seized his lands and as he advanced on Fenwick, Foliot

surrendered both the castle and his son Edmund as sureties that he would

present himself as a prisoner at York on an agreed day. It seems that Godberd,

Devyas and the other outlaws, like Robin and his men, must have slipped away.

When Foliot appeared before the king at Westminster, he

was able to give the names of twelve barons as guarantors for his behaviour.

With that he appeared in the Court of the King’s Bench on the 13th

October and the king instructed the sheriff to return his lands to him.

Jordan Farm near the site of the castle.

Trying to identify the ballad heroes and events in the Robin Hood legend is

impossible. But there are some interesting parallels here between the

historical evidence and the Geste of Robyn Hode. What is also intriguing is the location of the

Foliot lands, first pointed out by Professor J. C. Holt in his ‘Robin Hood’. Apart from his properties on the eastern side

of Sherwood at Wellow and Grimston, Sir Richard Foliot also held lands near

another area with strong connections to the Robin Hood legend - Wentbridge.

These places were in the valley of the Went at Norton, Stubbs and Fenwick.

Barnsdale, Robin’s other traditional haunt; lay just five miles from Fenwick. This link between the Foliot lands near Sherwood

and Barnsdale could explain how the legend was transmitted between his various

households and the locations of the ballad hero were conflated. Holt put it

rather romantically when he described how Sir Richard Foliot, ‘from his castle

at Fenwick, on a spring evening, would see the sun go down over Barnsdale, no

more than five miles away.’

Castles of Nottinghamshire... James Wright (2008)

On The Trail of Robin Hood...Richard de Vries (1988)

Robin Hood...J.C. Holt (1982 and 1989)

Robin Hood and the Lords of Wellow... Tony Molyneux-Smith

(1998)

Robin Hood...David Baldwin (2010)

The Birth of English

After having such a good response recently with my post on the medieval town of Nottingham, I have decided to continue with a similar theme. But this time it is inspired by a fantastic series called ‘The Norman’s’ by Professor Robert Bartlett. In my post last week we saw how the town of Nottingham was originally divided into two boroughs, one Saxon and one Norman. Each grew up alongside each other and eventually developed into the city we know today. This reflects how the English language first evolved, from its Saxon and Norman roots, to become one of the most influential languages in the world.

The Norman Conquest in 1066 brought a small mainly male group to power in England, a ruling elite of perhaps no more than 10,000 men. Intermarriage was common and the children of these Anglo-Norman marriages spoke ‘English’ because their mothers or wet-nurses were ‘English’ and the French and English languages are still playing out that dance that they began in 1066.

In the three centuries that followed the Conquest, thousands of French words entered the English language. First they were the words of power, politics and law (empire, govern, authority). But soon the language reflected Norman influence in every aspect of life.

Some of the new words were very important like, ‘war’, ‘peace’, ‘justice’ and ‘court’ and the reason the modern English language has so many different words for the same thing, is that the Normans introduced French alternatives. So ‘Royal’ derived from the French-‘kingly’ or ‘queenly’ from the ‘old English’ and the same with ‘country’ (French), land (English), ‘amorous’ (French), loving (English).

One of the things that make Anglo Saxon history seem strange or distant to us is the unfamiliarity of the names........ the Ethelbert’s’ and Egbert’s’. The Norman names, William, Henry, Richard and Robert caught on amongst the conquered and endure to this day. The ruling elite set the fashion; soon William was the most common male name in England even amongst the peasantry. Surnames that begin with ‘Fitz’ go back to the Norman practice of using ‘Fils’, meaning ‘son of’ as part of the name, giving us ‘Fitzsimons’ as ‘son of Simon’ or ‘Fitzgerald’, ‘son of Gerald.’

The languages were blending together, but French remained the tongue of the ruling class and nowhere are the class divisions clearer than with meat and drink. ‘Pig ’is English, ‘pork’ is French, ‘sheep’ is English, ‘mutton’ is French. So when it’s in a cold field covered in dung, its name is in English. When it has been cooked, carved and put on the table with a glass of wine, its referred to in French!

The association with ‘Frenchness’ with the English upper classes and the Saxon with the coarseness and vulgarity is one of the Norman’s enduring legacies. But over the decades the cultural distinction between Norman and Saxon gradually evolved and prospered to become one of the most influential languages in the world.

About a hundred years after the Battle of Hastings, the king’s treasurer Richard Fitz Neal wrote that ‘with the Normans and English living side by side and intermarrying the peoples have become so mingled that nowadays it is impossible to tell who is of Norman descent.’ And French the ‘language of power’ of the Norman’s, was by the 1500’s just a foreign tongue to be learned at school.

Medieval Nottingham

Above is an excellent map of the medieval layout of the medieval town of Nottingham, showing the original French and English boroughs. Robin Hood would have been familiar with this!

After the Norman Conquest, King William ordered a castle to be built on the huge rocky red sandstone, on the site of the original Danish tower, to the south-west of the settlement. It was originally made of wood and later re-built in stone in the twelfth century. Nottingham Castle remained outside the towns boundaries until the nineteenth century.

So a Norman settlement grew up around the shelter of the new wooden castle, leaving the Saxons largely undisturbed in their area around St. Mary’s Hill. For administrative purposes, two boroughs were set up, one French and one English; each had its own language and customs with a boundary wall running through the market place. To this day two maces are borne before the Sheriff of Nottingham, representing these two boroughs. The church of St. Peter was founded alongside St. Nicholas, both were in the French borough, whilst the pre-conquest church of St. Mary’s , visited by Robin Hood in the medieval ballad ‘Robin Hood and the Monk’, was in the English.

Under this Norman protection in 1086 the two boroughs had between 600-800 people. The first of the Plantagenet king’s, Henry II commenced to re-build the castle and its fortifications around the town in stone. He also gave Nottingham its first Royal Charter in 1154 allowing the Burgesses (leading citizens) to try thieves, levy tolls on visiting traders and hold markets on Fridays and Saturdays. This charter also gave them the monopoly in the working of dyed cloth within a radius of ten miles.

The Market Square (the largest in England) quickly became a focal point of the town, it also had an annual fair and from 1284 Edward I permitted extra fair days and one of these days became what we now know as Goose Fair, when people from as far away as Yorkshire would come for the two day event.

During the medieval period, Nottingham’s main industry was wool manufacture. But there were many craftsmen in the town and some of those occupations can be identified by the remains of its old street names, such as Wheelwright Street, Pilcher Gate, Boot Lane, Bridlesmith Gate, Blow Bladder Street, Gridlesmith Gate, and Fletcher Gate.

To read more about Nottingham please click here.

Robin Hood's Dungeon

The dungeon believed to have housed Robin Hood when he was caught by the Sheriff of Nottingham is to be surveyed using a laser. It is part of a major project to explore every cave in Nottingham. Robin Hood is believed to have been held captive in an oubliette (underground dungeon) located at what is now the Galleries of Justice.

The Nottingham Caves Survey is being conducted by archaeologists based at the University of Nottingham.

The two year project, costing £250,000, has been funded by the Greater Nottingham Partnership, East Midlands Development Agency, English Heritage, the University of Nottingham and Nottingham City Council.

Experts from Trent and Peak Archaeology will use a 3D laser scanner to produce a three dimensional record of more than 450 sandstone caves around Nottingham from which a virtual representation can be made.

David Knight, Head of Research at the Trent and Peak unit, said there will be no actual excavations just the use of the laser.

"The aim is to increase the tourist potential of these sites. The scanning will also make them visible 'virtually' which is good in terms of public access because a lot of them are health hazards.

"That's one of the problems with these caves - they're very impressive but access is fairly difficult. You can imagine the health and safety issues are quite significant."

The last major survey of Nottingham's caves was in the 1980s. The British Geological Survey (BGS) documented all known caves under the city.The Nottingham Caves Survey will update the information that made up the BGS's Register of Caves.

David Knight said: "Once we've done the whole lot we'll be in a position to rank them in order of significance and make a decision on which caves may or may not be opened."

The area which now makes up Nottingham city centre was once known as Tiggua Cobaucc, which means 'place of caves'.

The caves date back to the medieval period and possibly earlier. Over the years they have been used as dungeons, beer cellars, cess-pits, tanneries and air-raid shelters.

Today the most famous include the City of Caves in the Broadmarsh Centre, Mortimer's Hole beneath the Castle, the oubliette at the Galleries of Justice, and the cave-restaurant at the Hand and Heart pub on Derby Road and the cellar-caves at the Trip to Jerusalem pub.

The Forest Lodge, Edwinstowe, Nottinghamshire

Back in June I spent a lovely weekend in the small village of Edwinstowe in Nottinghamshire. I stayed at a lovely old coaching inn called The Forest Lodge which is about 5 minutes walking distance from the entrance to the Sherwood Forest Visitor Centre.

The owners of The Forest Lodge were very welcoming and the quality of the service and food was exceptional. There is ample parking in the forecourt and the hotel lies almost opposite St. Mary’s Church, where legend states that Robin Hood married Maid Marian. I thoroughly recommend The Forest Lodge and hope to make another visit as soon as I can. Their website is at: http://www.forestlodgehotel.co.uk/main.html

Wellow May Day

Robin Hood is inextricably linked with the May and Summer Games performed throughout England and Scotland during the 16th century. The surviving church wardens accounts reveal that Robin along with the ‘Maid’ Marian often took on the role of ‘King and Queen’ of the revels accompanied by Friar Tuck and the rest of the gang of merry men.

Sadly these traditional celebrations have been on the decline for many years, so I was thrilled to receive these pictures from Albie of the ‘May Day’ festival in his village of Wellow in Nottinghamshire. I feel it is very important that these ancient traditions survive.

Albie said:

“Basically, today was the 60th anniversary of the dancing returning after WW2. The old May queens were from 1950 through to last year’s representing each decade. The youngsters are all from the village I believe.

This tradition of the May Queen and dancing would have been well known to Robin Hood. There was a similar scene from the Robin of Sherwood TV series I believe. It is a tradition we must keep. So much has been lost, this cannot be left to fade into history, although I live 3 miles from Wellow this is the first time I have been to May Day since 1978 (I think). There were a massive number of people there today, more than is normal/ don’t know whether this is due to the Crowe film but good to see so many there.”

I travelled through Wellow quite recently, but alas didn’t have time to look around. The name Wellow is derived from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Wehag’ which means ‘enclosure by a well or spring’ and this idyllic village has many connections with Robin Hood.

According to the book 'Robin Hood and the Lords of Wellow' by Tony Molyneux-Smith, its unusually shaped village green holds more secrets than would appear at first glance. Although the green has changed over the centuries, as houses were built and the road to Eakring constructed, his book says that it is still possible to see that its original shape would have formed a perfect triangle - the shape of an arrow head - which points directly at the castle of the Sheriff of Nottingham!

Wellow was given permission to hold a market in 1268 and has one of only three permanent maypoles in England. Surviving records show that a maypole stood on the green in 1856 but the village tradition goes back much earlier and the local 12th century church celebrated this fact, when it recently commissioned a beautiful stained glass window of the Wellow maypole.

Sadly these traditional celebrations have been on the decline for many years, so I was thrilled to receive these pictures from Albie of the ‘May Day’ festival in his village of Wellow in Nottinghamshire. I feel it is very important that these ancient traditions survive.

Albie said:

“Basically, today was the 60th anniversary of the dancing returning after WW2. The old May queens were from 1950 through to last year’s representing each decade. The youngsters are all from the village I believe.

This tradition of the May Queen and dancing would have been well known to Robin Hood. There was a similar scene from the Robin of Sherwood TV series I believe. It is a tradition we must keep. So much has been lost, this cannot be left to fade into history, although I live 3 miles from Wellow this is the first time I have been to May Day since 1978 (I think). There were a massive number of people there today, more than is normal/ don’t know whether this is due to the Crowe film but good to see so many there.”

The Old York Road and Robin Hood's Cave

Once again Albie has sent in some great pictures of ‘Robin Hood Country,’ along with interesting details of the locations. A while ago I explained that I was very interested in re-discovering some of the ancient track ways that led through the parts of Sherwood Forest. So this time Albie takes us along part of the Old York Road in Nottinghamshire.

The main London to York road, also known the Great North Way, ran straight through Sherwood, and travellers were often at the mercy of robbers living outside of the law. Hence the name ‘outlaws’. It was such an important route in early times that it was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086:

“In Nottingham the River Trent and the dyke and the road to York are so protected that if anyone hinders the passage of ships, or anyone ploughs or makes a ditch within two perches of the King’s road, he has to pay a fine of £8.”

Here are Albie’s descriptions of his pictures:

The River Maun Looking North

"This was taken from the hump back bridge on the lane (Whitewater Lane) that runs between Walesby and the A614. The river, known as both the Maun and Whitewater locally, drains from Mansfield before meeting the Meden a couple of miles further north. The bridge was built in 1859 for the estate workers at Thoresby Hall to travel from Walesby and Ollerton without having to ford the river.

Old York Road Looking West

Old York Road Looking North

These are taken at the point where the Old York Road crosses the lane to Walesby around 100 metres from the hump back bridge. The road south goes into New Ollerton and onwards to Old Ollerton through a large housing estate built for the now demolished Ollerton Coal mine. The picture north is where the road becomes a foot path bordering the Walesby Forest Scout Centre to the east and the River Maun to the west.

The York Road, North at Robin Hood's Cave

These pictures were taken above and at the side of Robin Hood’s Cave which is obscured by vegetation. Local legends have it that Robin and his outlaw band would hide here below the main road above ready to ambush the unwary traveller. A local historian reckoned the caves have been used since the retreat of glaciers at the end on the Ice Age. This historian, now deceased, maintained that Walesby and parish is the oldest continually inhabited place in Europe though this would be difficult to prove. Artefacts dating to the Bronze Age have been found around the village as have numerous Roman coins.”

Robin Hood's Cave

Robin Hood's Cave 2

Many thanks Albie. I can’t help thinking of Carmen Dillon’s set design for Disney’s Story of Robin Hood when I see those pictures of Robin Hood’s Cave. Also of the outlaws looking down, as the rich travellers made their nervous way along the York Road.

Nottinghamshire in 1693

This amazing map of 'Robin Hood Country' was sent in by Albie. It shows Nottinghamshire in 1693 and clearly shows the surviving remants of the ancient Sherwood Forest and some of the old roads through the shire.

The 'Carps' and the Ghosts

Albie is lucky enough to live, in what is known as ‘Robin Hood Country’-Nottinghamshire. He has recently provided some stunning pictures of Sherwood Forest which were very popular with my readers. This time Albie has very kindly sent in a fascinating history of two of his local taverns in the Nottinghamshire village of Walesby, The Carpenters Arms and The Red Lion.

"The old and new pictures show the Carpenters Arms public house in Walesby. The older picture was taken in the early years of the 20th century and was copied from one of a series of post cards popular in that era. The pub was built in 1830 and is currently owned by the Everard’s brewery of Leicester. The interior has been re-styled over the years with the accommodation for the landlord now being upstairs, previously being downstairs around the current fireplace on the right of the building.

The man standing at the top of the stairs was possibly the landlord at the time. The cottage to the right (furthest cottage) was the original Methodist chapel in the village. It is known that the son of the founder of Methodism, Charles Wesley, preached there, and possibly Charles himself. The chapel now forms part of the house living area. The house in the right foreground is of a similar date (1770’s) or slightly later. Behind the pub, but obscured by it, near the top of the hill was the bakery which is also from the same era.

The Carpenters is not the only pub in the village, the other being the Red Lion situated 400 yards down Main Street, which starts where the now demolished cottage is to the left of the pictures. The Lion has a large portion of the building dating to some 400 years ago and is near the heart of the old village.

Although only 180 years old at the time of writing, the Carps (as it is known locally) main claim to fame is its resident ghosts. The most seen one is that of the Grey Lady. She has been seen by many people (including this author!) and wears a Victorian style bonnet and long dress. Often seen upstairs in the landlords apartment, she has also been seen by regulars in the bar area. It is unknown who she was but is a ‘friendly’ ghost. A second ‘visitor’ is a gentleman wearing tweed clothing with a red complexion. He is thought to be a former landlord who was accidentally killed when a shot gun went off in his kitchen area, in front of the fireplace in the current bar area. This happened in 1947.

A third reported ghost is to be found in the cellar situated below the steps where the landlord stands in the old picture. The cellar is low, cramped and eerie as there is no natural light. A rumour persists that a previous landlord hung himself down there but no proof of this exists. The stories could have more to do with the fact the pub is built on an old crossroads. In medieval times, criminals were hanged and executed at crossroads outside of inhabited areas (the old village centre being 400 yards away at that time). Once dead, the bodies would be buried at the crossroad so their spirits would not know which way to wander and hence enter the village to haunt the locals! It is likely this crossroad was used for such purposes in the distant past.

Another legend of a 4th spectre is that of the White Lady. She reputedly walks from Rufford Abbey into Edwinstowe. There she turns right and heads towards the current junction of the A614 and the A616 Sheffield – Newark road and onwards to the carps at Walesby. She then turns back to return to Rufford, thus completing a triangle of around 12 miles distance in total. Theory is she was a lover of a monk from the Abbey (dissolved with the other entire Abbeys by Henry VIII in the 1540’s). Why she would come from Edwinstowe to Walesby is confusing but when the Abbey was shut down by Henry, one of the monks from there became the vicar of St Edmunds Church in Walesby. No one has seen this ghost for a number of years.”

I recently asked Albie where he saw ‘The White Lady?’

“I saw the ghost whilst sitting at the bar one evening. I'd only just sat down and when I looked up something caught my eye. This grey figure glided from the right of the bar from the eating area and dissolved by the front door. I have also seen another figure sat on one of the bench seats inside which stayed a few moments before fading away. A number of times items on the back of the bar have either moved or flown across the serving area - a pen did so when I was there when no one was stood anywhere near the bar. Nothing malevolent, just strange things and I can add that a previous landlord saw the ‘Grey Lady’ and ‘Tweed Man’ standing at the foot of the accommodation stairs together. His father also the Grey Lady but never said anything about. When he did (rather sheepishly) his son said, 'yeah many have see it, you are not on your own'.

Terry (father) was a university lecturer so a fairly sober and learned man. Take this one with a pinch of salt, the current landlords partner (who is from Thailand) has both seen and talked to the Grey Lady. She apparently came and sat down at the end of her bed and talked with his partner.

Not so sure how valid the last story is (though Neil, our current mine host says it is true and he is not one for telling tall stories) but the others are!”

Albie-May 2010

Albie has very kindly sent in more details about the local history and countryside around Sherwood and Nottinghamshire, which I will post very soon.

Nottingham's Caves

Above is a publicity photo of (right to left) Richard Todd, Lawrence Watkin (script writer), Perce Pearce (producer) and Dr. Charles Beard (research advisor)during their fact-finding trip to Nottingham, before making the Story of Robin Hood. One of the historical sights that Disney’s team of researchers saw when they visited Nottingham, was the remarkable rock-hewn caves and passages that are underneath the city. Some of the publicity shots can be seen in the short promotional film The Riddle of Robin Hood, one in particular, included Richard Todd (smoking a pipe) emerging from the small man-made opening of a cavern.

Above is a publicity photo of (right to left) Richard Todd, Lawrence Watkin (script writer), Perce Pearce (producer) and Dr. Charles Beard (research advisor)during their fact-finding trip to Nottingham, before making the Story of Robin Hood. One of the historical sights that Disney’s team of researchers saw when they visited Nottingham, was the remarkable rock-hewn caves and passages that are underneath the city. Some of the publicity shots can be seen in the short promotional film The Riddle of Robin Hood, one in particular, included Richard Todd (smoking a pipe) emerging from the small man-made opening of a cavern.Nottingham’s earliest reference to its caves comes in the year 868 AD in Asser’s Life of King Alfred, when the area is described as Tiggun Cobaucc-Place of Caves. Some of them are natural; others are man-made, cut from the solid Bunter Sandstone ridge (also known as Sherwood Sandstone) upon which the city sits. It is ideal for excavation and those early dwellers used the simplest hand-held tools to cut into the rock to make a dwelling. Gradually extra chambers were added for storage and working in. Soon this remarkable honeycomb cave system spread out for about five miles around the city. The bulk of them produced during the Anglo-Saxon period.

Because Sandstone does not burn, craftsmen and traders soon realized the potential of the Nottingham caves. On Bridlesmith Gate, blacksmiths used the caves for their workshops, the fishmongers in Fisher Gate and the Butchers of Goose Gate used them for storage. The constant steady temperature of the caves was ideal for the brewing of ale. Nottingham ale became renowned. Barley was brought in from the Vale of Belvoir and mixed with Nottingham’s natural gypsum rich water. After the ale was left to mature in the caves it was exported throughout places like Mercia.

Most of the old local public houses use rock cellars. Today, you can still see in The Trip To Jerusalem, cellars cut deep back into the castle rock, ventilating shafts, a speaking tube bored through it and a chimney climbing through the rock forty seven feet above the chamber, all evidence of its brewing past.

During the construction of the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre, many of Nottingham’s man-made caves were nearly lost forever. But two caves, originally cut into the cliff face, now form, what is known as the City of Caves attraction beneath the shopping mall. The tour includes a unique medieval underground Tannery and the Pillar Cave, so called because of the large column, which supports the roof. Both caves were used like many of the others, during WWII as air-raid shelters.

It was in the well of the Pillar Cave that a King John groat (a silver coin, worth four English pennies) was found.

These remarkable caves no doubt inspired Carmen Dillon and the rest of the Disney team of researchers during their fact-finding visit to Nottingham for the Story of Robin Hood. So I am sure it is no coincidence that Robin’s camp, in Disney’s Robin Hood is a series of caves, hidden deep in Sherwood Forest.

The Gough Map

Our earliest historical glimpse of the town of Nottingham and Sherwood Forest can be seen on what is known as the Gough Map. It is now held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford and is the oldest road map of Great Britain. Very little is known about its origins. It was part of a collection of maps and drawings owned by the antiquarian Richard Gough (1735-1809), who bought the map for half a crown (12 ½ pence) in a sale in 1774. He later donated his whole collection of books and manuscripts (including this map) to Oxford University Library, under the terms of his will in 1809.

Our earliest historical glimpse of the town of Nottingham and Sherwood Forest can be seen on what is known as the Gough Map. It is now held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford and is the oldest road map of Great Britain. Very little is known about its origins. It was part of a collection of maps and drawings owned by the antiquarian Richard Gough (1735-1809), who bought the map for half a crown (12 ½ pence) in a sale in 1774. He later donated his whole collection of books and manuscripts (including this map) to Oxford University Library, under the terms of his will in 1809. The map measures 115 x 56 cm and is made of two skins of vellum. The unknown map-maker used pen and ink washes to depict the towns and villages, with the roads marked in red. The distance between each town is also included in Roman numerals.

Clues to the date of the creation of the map can only be found by analyzing the handwriting and the historical changes to some of the place names inscribed by its mysterious artist. Therefore it is generally put at about 1360.

The medieval artist has depicted the Royal Forest of Sherwood as two intertwined trees and just above can be seen the walled town of Nottingham.

Nottingham c.1610-1611

This the earliest depiction of the town of Nottingham, showing us the medieval layout that Robin Hood would have recognised. It is an engraving by the Flemish artist, Jodocus Hondius Sr. for John Speed's compilation of maps called 'The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britayne' (c.1611). It was in fact the first atlas of the British Isles.

This the earliest depiction of the town of Nottingham, showing us the medieval layout that Robin Hood would have recognised. It is an engraving by the Flemish artist, Jodocus Hondius Sr. for John Speed's compilation of maps called 'The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britayne' (c.1611). It was in fact the first atlas of the British Isles.Nottingham Castle 1068-1100

Nottingham Castle is an important element in Walt Disney’s live-action film, ‘The Story of Robin Hood’. As Helen Phillips explains in her paper ‘Forest, Town and Road’ -for the lectures on ‘Robin Hood in Popular Culture,' -the castle, with its massive size and impregnability, gained new prominence with the advent of film, partly because of its potential for sheer visual impact and also because it offered new special theatricality through the shift to visual narrative. This is certainly the case in the Douglas Fairbanks silent version in 1922, the Michael Curtiz classic of 1938 and of course the ‘Story of Robin Hood’ in 1952.

In the planning stages for Disney’s motion picture, Ken Annakin, Carmen Dillon, Perce Pearce and other members of the production team, spent three days with the great man himself, in Sherwood Forest and Nottinghamshire. They looked over many of the sights associated with the outlaw, but Disney was disappointed, (like so many tourists) to see many of the castles of the midlands in ruins. Nottingham Castle was almost completely destroyed with gunpowder and pick, during the Civil War of 1642-1660. All that remains today for visitors to see, is an outer portion of the barbican, used as an entrance, a small portion of the walls of the outer ballium and the base of what was known as Richard’s Tower. So art director Carmen Dillon recommended the up and coming matte artist, Peter Ellenshaw to work on creating medieval Nottingham and its castle for Disney’s live-action motion picture.

So what was the real Nottingham Castle like?

During the summer of 1068, William the Conqueror (pictured above) rode north to deal with a Saxon rebellion. He stopped at Nottingham to assess its strategic value and decided to build a castle on the huge rocky red sandstone, above the meadows of the River Trent. He left William Peveril instructions for a motte and bailey type castle to be built, ‘in a style that was unknown before’, on the 130 ft high rock. The tower of which would be in an impregnable position.

Nottingham Castle is not mentioned in the Domesday Book, but this may have been due to a delay in construction because of ‘opposition from the men of Nottingham.’ When William re-visited Nottingham a year later the townsmen had been forced into subjection and were compelled to assist in building the new fortress with a handful of Norman supervisors. Peveril was rewarded for his services with a ‘fief’ known as ‘the Honour of Nottingham’ made up from lands in six shires including Sherwood Forest and the Peak.

Castles were unknown in England before the Norman Conquest in 1066. But within five years of the Battle of Hastings, thirty castles were built across the country. The motte, a high mound usually constructed from the earth dug out of the deep surrounding ditch, was constructed on the highest part of the rock. On it would be wooden buildings and perhaps, a wooden watch tower or keep. Below the motte, to the north, was the bailey similarly enclosed by a wooden palisade on an earth rampart. Curling around to the south of the palisade of wooden stakes was the River Leen, which had probably been diverted as an additional form of defence, to supply the garrison with water and power the Castle’s mills.

The building would have been probably two or three storeys high and reached by an exterior stairway or wooden ladder. The first floor would have included the Great Hall, sleeping quarters and living rooms of the Lord, including the chapel. But, because the first Nottingham Castle was constructed mainly of wood, cooking would have been done outside as a

fire precaution.

The location for a castle at Nottingham, was ideal for two reasons. First because the rock provided an easily defensible site dominating the country around, including the Saxon town huddled around St. Mary’s Church in what is now the Lace market. Second, Nottingham was on the main road between London and the North and was also only a mile from the River Trent, the dividing line between the North and South of England, so it could be easily supplied and reinforced. Because of its ideal situation, Nottingham castle became the principal royal fortress in the Midlands for five centuries.

The local population would have been forced to build their Conqueror’s castle in whatever materials were available. The rock provided a natural motte or mound and the original walls enclosing the bailey’s or yards, though probably being of wood, may have been supplemented by stone dug out of the surrounding ditch. In the highest part of the Castle, the upper bailey, were rooms and a watch tower. Beyond, to the north, was another bailey, the Middle Bailey. This was enclosed by a palisade placed on the top of a rampart formed by the sand excavated from the surrounding new moat. Subjugation of the local population was completed by the building of a new Norman Town in the shadow of the castle with its own market place-the present Market Square. Land was also taken to the west of the castle to make a park, which would be stocked with deer to provide food and sport, whilst to the south, the King’s Meadow would be used for grazing.

Because the motte was natural rock it would not be necessary to wait for the ground to settle before building high stone walls and towers on its summit. If these walls were not originally built of stone they may have been by the reign of Henry I (1100-35). These great stone walls with towers rising as it were, from the very rock itself and visible for miles in every direction, must have awed the local population. Below it to the north were the palisade walls of the Middle Bailey (now the Castle Green) and beyond them to the north and east more land was enclosed to form the Outer Bailey, though exactly when this was first enclosed we do not know.

© Clement of the Glen 2008

Nottingham's Unique Silver Penny

This unique old silver penny dating from the eleventh century (both sides are shown above) now belongs to Nottingham City Council. It was either struck at Shelford, near Radcliffe-On-Trent in Nottinghamshire, or on Bridlesmith Gate in Nottingham. Although the small 1.55mm diameter coin is very thin and fragile and not complete, you can still see the image of a newly crowned William the Conqueror (c.1028-1087) on one side, unusually facing forward carrying a sceptre patte and a sceptre botonne. The inscription partly missing reads : WILLIAM REX ANGLOR– William King of England.

On the reverse, there is a cross fleury with an annulet in the centre over saltire botonne with the legend, M[AN] ON SNOTINGI. ‘M’ could indicate that the coin was struck by the moneyer Manna and SNOTINGI ( Snotting) was the ancient name of Nottingham. It cost Nottingham Council £860 to bring this silver penny home.

Domesday Nottingham

Robin Hood is often described as a Saxon, competing against his oppressive Norman overlords in various films and novels. So what was Nottingham, the place most associated with the outlaw like, when the Normans began to rule England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The best way to find out, is to look in the Domesday Book, an incredibly unique snapshot of life in late eleventh century England.

Great Domesday was commissioned by William I (the Conqueror) at his Christmas Court in 1085 and the whole enormous work of collecting the information and turning it into the book that survives today, took under two years to complete. A fantastic achievement and a tribute to the political power and formidable will of William the Conqueror. This book is today preserved at the Public Record Office at Kew, but for many centuries it was held at Winchester the ancient Saxon capital of Wessex. It is not only written in Latin, but in a highly abbreviated form of Latin. It took approximately nine hundred sheepskins, soaked in lime and stretched over wooden frames, to make the parchment for the clerk, to give us a snapshot of a world, far different to the one we know today.

The Domesday survey was a detailed statement of lands held by the king and by his tenants and of the resources which went with those lands. It recorded which manors rightfully belonged to which estates, reducing the years of confusion between the Anglo-Saxons and their Norman conquerors . It also gave him the extant to which he could raise taxes! This illuminates a crucial time in our history, the settlement in England of William and his Norman and northern French followers. Local people likened this irreversible gathering of comprehensive information, to the Last Judgement, and by the late twelfth century this remarkable survey became known as Doomsday. Before that it was known as the Winchester Roll or King’s Roll.

Nottingham at this time, is recorded as:

Snoting(e)ham/quin: King’s land. The main landholders are listed as Hugh FitzBaldric; the Sheriff; Roger de Bully; William Peverel; Ralph Fitzhurbert; Geoffrey Alselin; Richard Frail.

A church is also listed, the original Saxon church of St Mary’s, later destroyed in the mid twelfth century. The number of burgesses given is 120 and the amount of families in Nottingham at this time can not have been more than 500.

Roger de Busli or Bully and William Peverel were William the Conqueror’s two great tenants-in-chief. Some believe that Peverel was an illegitimate son of the Conquror. The Domesday Book shows that after the Conquest, Peverel was rewarded for his invovement in the Battle of Hastings with 162 lordships.

After stopping at Nottingham on his way north, William I had given Peverel instructions for a motte and bailey type ‘royal’ castle to be built on the 130 ft. high rock overlooking the town, in the king’s name. Over the following centuries the wooden fortress would be re-built in stone. The castle would be a strategic key to the midlands. Peverel was later made constable of Nottingham Castle and rewarded with a ‘fief’, known as the Honour of Nottingham, which included Sherwood Forest, the High Peak and lands in six shires, to support him. During the reign of King John, the sheriff’s of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire became custodians of land that became known as the Honour of Peverel.

The ‘Peverel Court’ was held in Nottingham up until 1321. It was a Court of Pleas for the recovery of small debts and for damages of trespass and had jurisdiction over 127 towns and villages around the shire. In Basford stood Peverel’s Gaol, founded in 1113 and used for the imprisonment of debtors by the successive sheriffs of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

Roger de Busli was rewarded by King William I, like William Peverel for his assistance at the Battle of Hastings and was granted holdings in six English counties, including 174 estates in Nottinghamshire. Very little is known about him and he is described by some as famous in Domesday but nowhere else. His seat of power, became his manor house at Blyth in Nottinghamshire, described in the Domesday Book as:

Blyth (Blide) land of Roger de Busli 1 Bovate of land and the fourth part of 1 bovate taxable. Land for 1 plough. 4 villagers and 4 smallholders have 1 plough. Meadow 1 acre.

Blyth became one of only five designated sites in England, licensed by Richard I to hold tournaments. The area has been recently re-discovered in a field known locally as Terminings (tourneyings) Meadow on a tract of land between Blyth and Stirrup. The Pope had denounced these exhibitions of skill in arms, but Richard refused to be denied the ability to train his English knights to the level of skill of their counterparts on the continent.

Roger Busli also built Tickhill Castle an earthwork motte and bailey fortressfor the king, where he bestowed many great gifts to his followers, to the disadvantage and animosity of the original Saxon landowners.

If we look in the Domesday Book at some of the local villages that later become known as part of Sherwood Forest, we can see how the land was parcelled up between the new powerful Norman lords.

Edwinstowe, now the main modern tourist centre for Sherwood, was land owned by the king, Edenestou 1c. Of land taxable. Land for 2 ploughs. A church and a priest and 4 smallholders have 1 plough. Woodland pasture 1/2 league long and 1/2 wide. Clipstone (Clipestune) was land owned by Roger de Busli as was Cuckney (Chuchenai). Linby (Lidebi) belonged to William Peverel. Mansfield (Mamesfeld/Memmesfed was King’s land with, mill, fishery, 2 churches.

Nottinghamshire was originally included in the diocese and province of York up until 1836 and we see Blidworth (Blidworde) a village in Sherwood Forest, described as owned by the Archbishop of York before and after 1066. Oxton (Ostone/tune) was also land held by the Archbishop of York and the under tenant was Roger de Busli. Papplewick (Papleuuic) was held by William Peverel and Thoresby (Turesbi) was King’s land.

Sherwood Forest is first mentioned 68 years after the Domesday survey when it was controlled for the king by Peverel’s grandson (also called William). But this sandy infertile part of Nottinghamshire was probably afforested by William the Conquror, or his immediate successors, at a far earlier date.

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007

Robin Hood's Statue At Nottingham Castle

Four months after the Royal Premier of the film The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men in London, further up north in Nottingham, they unveiled a statue to their world famous outlaw, by the castle walls, in the presence of the Duchess of Portland.

Four months after the Royal Premier of the film The Story of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men in London, further up north in Nottingham, they unveiled a statue to their world famous outlaw, by the castle walls, in the presence of the Duchess of Portland.The ceremony took place on July 24th 1952 on Castle Green, in a specially landscaped area at the foot of Castle Rock, in the remains of the old moat, by local architect Cecil Howitt. The seven foot statue, including four bas-relief plaques were a gift to the city, by local businessman Philip E. Clay and was designed and cast out of half a ton of bronze, one inch thick, by Royal Acadamician, James Woodford (1893-1976) in his studio at Hampstead. Woodford was the son of a Lace designer and was born in Nottingham. He attended the Nottingham School of Art and after military service during the First World War he trained at the Royal College of Art in London.

A year after his statue of Robin Hood was unveiled at Nottingham Castle, James Woodford RA was commissioned to carve a set of ten heraldic figures out of Portland Stone, to be placed at the entrance of Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. These heraldic beasts were selected from the armorial bearings of her royal ancestors and can be seen today along the walkway between Palm House and the pond at Kew Gardens.

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007

Roll Of High Sheriff's of Nottinghamshire And Derbyshire

Nottinghamshire ran under the same Shrievalty with Derbyshire until the 10th year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Below is a tentative list of those early Sheriff’s compiled from existing medieval documents.

1157: Sir Robert Fitz Ranulph

1170: William Fitz Ranulph

1189: Ralph Murdoc

1195: William Brewer

1204-8: Robert de Vieuxpont

1208-9: Gerard De Athee

1209: Philip Marc

1224: Ralph Fitz Nicholas

1233: (April) Eustace of Lowdham

1233: (October) Simon De Hedon

1235: Robert De Vavasour

1236: Hugh Fitz Ralph

1240: Robert De Vavasour

1255: Sir Walter De Eastwood

1255: (May) Roger De Lovetot

1258: Simon De Hedon

1260: Simon De Asselacton (Aslockton)

1264: John De Grey

1265: Reginald De Grey

1266: Hugh De Stapleford

1267: Simon De Hedon

1267: (Michaelmas) Gerard De Hedon/Hugh De Stapleford

1268: Hugh De Stapelford

1270: Walter Archbishop of York

1271: Hugh De Babinton (Under Sheriff to Walter, Archbishop of York)

1271: (Michaelmass) Walter Archbishop of York

1274: Walter De Stirkelegh

1278: Reginald De Grey

1278: (Michaelmass) Gervasse De Willesford

1285: John De Anesle

1290: Gervase De Clifton

1290: (Michaelmas) William De Chaddewich

1318: Henry De Faucumberg

1319: John Darcy

1323: Henry De Faucumberg

1327: Robert De Ingram

1329: Henry Faucumberg/ Edmund De Cressy

1330: John Bret

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)